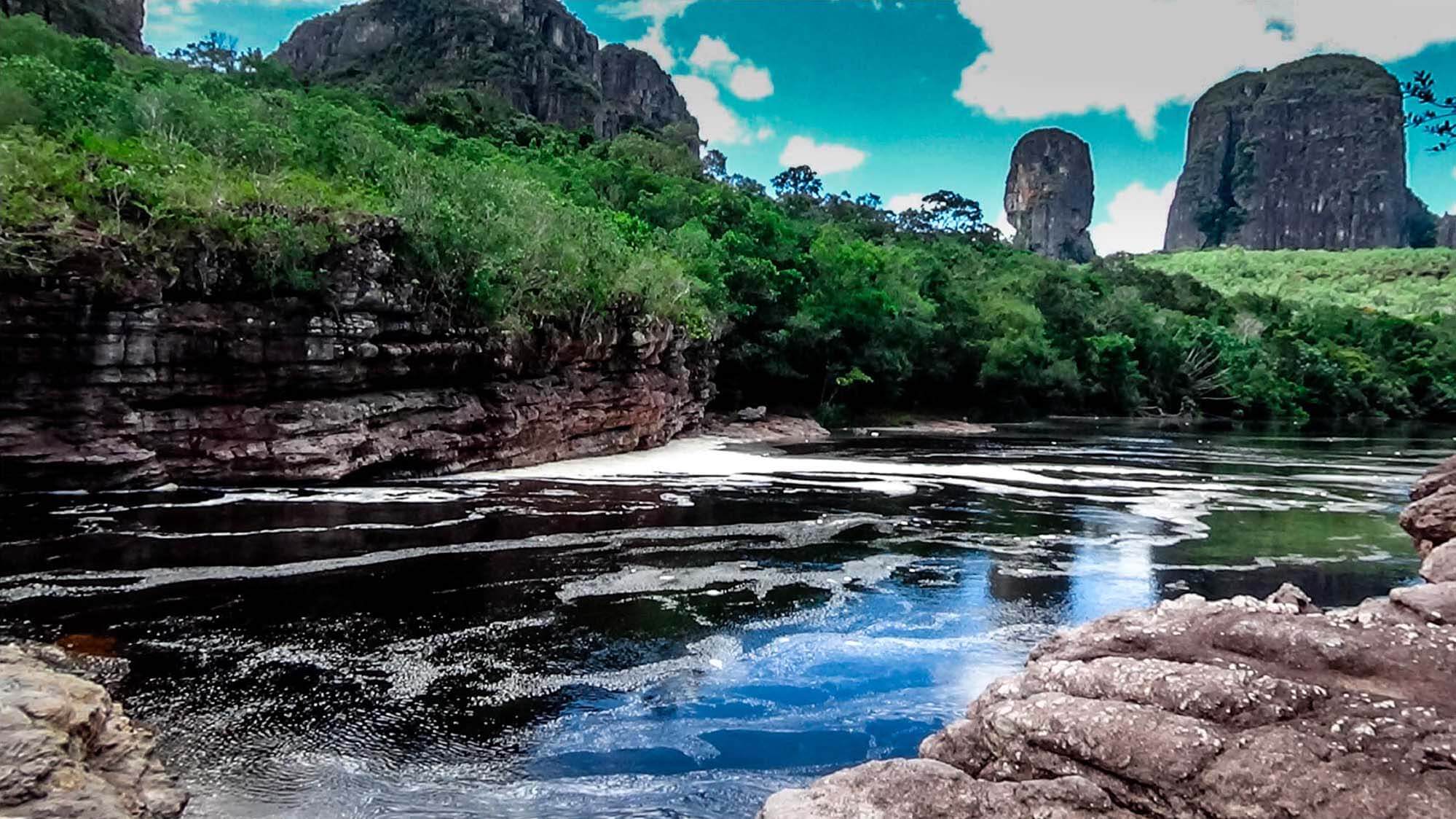

Peasant hands wielding machetes cut down the jungle to plant the sacred leaf of the Andes. Five or six peasants would level a hectare of forest every day. They would then burn whatever they had razed and place the seed right after. A year later, the first yield would be ready. Perga’s father was –he probably still is—one of those peasants who picked the leaves of the coca plants with his bare hands until his skin, just like the jungle, opened in gorges. The wife of that peasant, young as she was, was pregnant once again. One day in March 1983, she unexpectedly went into labor in the ranch. The child was two months early, though the truth was that nobody was really keeping track of the time. When the man stepped into the room, his wife was panting. The baby was by her side, connected to her by the umbilical cord.