Landa. Lan-da, the word falls through the throat as it travels down the jaw. Upon hearing it, there are some who might think of Africa, of Malawi, Tanzania. Lwanda, Luanda, Landa. Though there is a Landa Hill in the savannahs of Western Africa, in the midst of National Park in the northeast of Nigeria, the last name Landa seems to come from another continent. There are those who mention Italy, but the majority talk about Euskal Herria, the Basque Country, as it’s referred to in English: Landa, the name of a town in Ubarrundia, a sandy moorland, a land of wild plants, an illiterate plain.

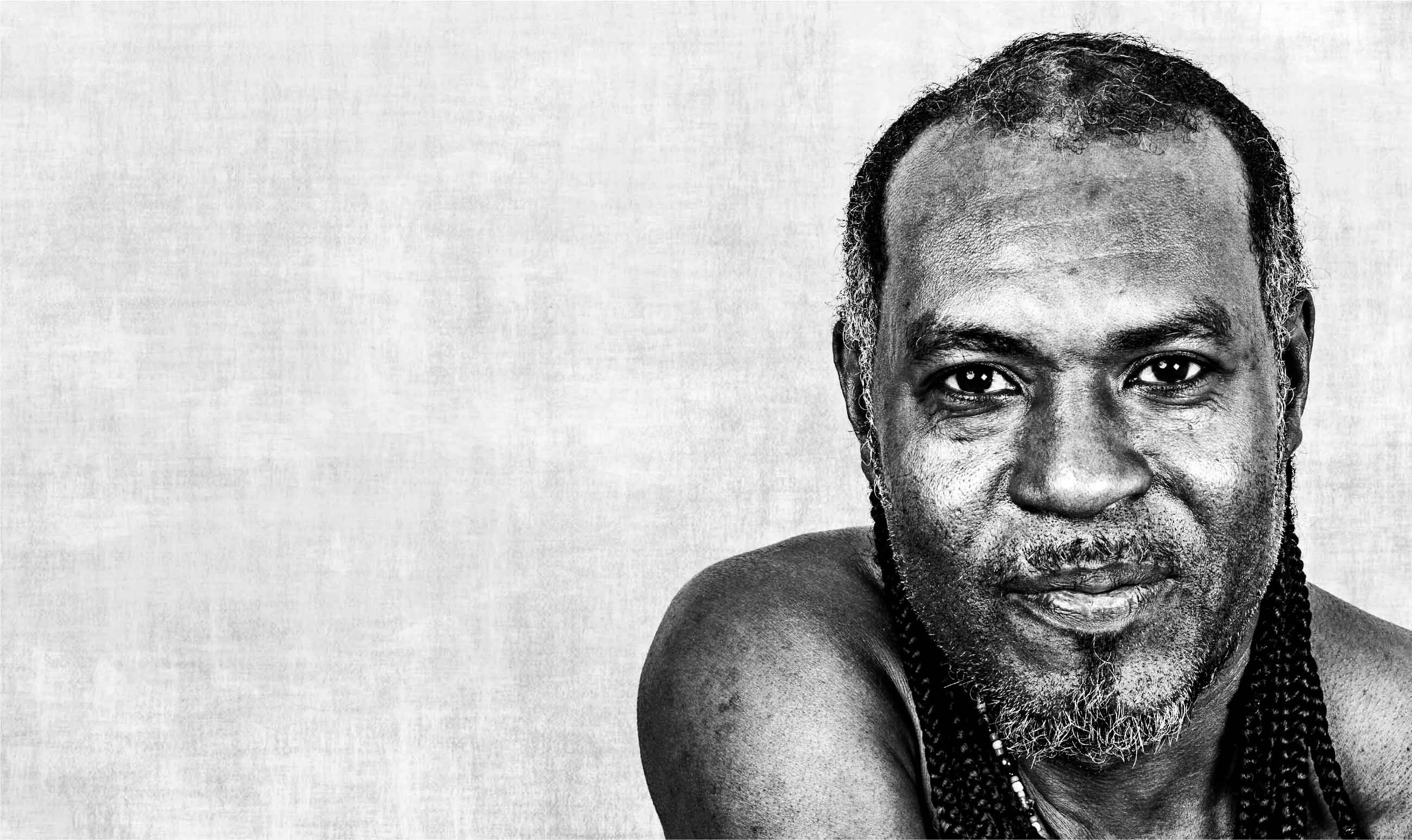

Landa is also a tall, black man with long braided hair who was born in the county of Aguacate, in the jungle near Tumaco, between the Mexican River and the Mira River. He is called Wilfrido, Wilfrido Landa. In newspapers, he appeared dressed all in white with a rastafari hat that hid half of his braids; a long collar of variegated beads and some grey hairs in his sideburns, visible under the black, red, green, and yellow fabric. Landa was seen posing rigidly next to others who came from all parts of Colombia to share stories of war and pain. He was seen shaking hands with government officials and guerrillas.

Landa has also been seen smiling when coming off planes in different airports in the United States; concentrated and anxious in Havana; frightened and breathless in Cali and Bogota.

Landa’s travels start in the water, in canoes carved from chachajo trunks, from chaquiro or purga trees. They also start on land –traveling on foot through the barely drawn roads in the canyons of Aguacate, one of 15 counties that nowadays make up a land owned collectively by the black communities: the Rescate-Las Varas Community Council.

His mom: a farmer, a baker, a nurse, a midwife and godmother to hundreds of children who were born in Aguacate. His father: a farmer and, with a flashlight in hand, a watchman for Mar Agricola, a shrimp farming company, until 30 years ago when, one day in March, he was found floating in the waters with three gunshot wounds.

After his old man died, Landa quit school and began his travels, his first big journey: three years travelling the departments of Valle del Cauca and Putumayo. “I labored as a construction worker: walls, plates, patches –lax things.” In 2000, Aguacate saw him return. Soledad also did. “The thing is that I didn’t come back yearning to finish high school, but rather wanting to continue with the marital subject. We moved together with Soledad and, in 2002, the girl Flor arrived.”

Before he left for what he calls his “three-year vacation,” Landa and other young people from the community had traveled the roads of the counties looking for the men and women of the territory, the black men and women like them. Landa and the others wanted to talk to those other black men and women about the legal possibility, unheard of until that time, of collectively titling that land, the same land they had inhabited for so long, the same land that was considered a “wasteland of the nation.” With the 1991 Constitution, Colombia acknowledged itself as a “multiethnic and pluricultural” nation. One of the basic rights that acknowledgment entailed was the right to establish territories where ethnically defined communities could exercise certain levels of autonomy. Before 1991, this legal figure already existed for indigenous communities, but not for black communities.

The Rescate-Las Varas Community Council was finally formed on March 14, 1999, when Landa was still traversing the roads of Putumayo, but after he came back he not only took of care of jumpstarting the land in Aguacate, planting African palm, and raising a house where he could live with Flor and Soledad; he also traveled to all nearby counties again, and, in 2007, he was elected as the Legal Representative of the Council. In 2010, in an assembly, he was reelected to his charge by the community.

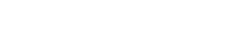

Tumaco-Bogotá, 2013

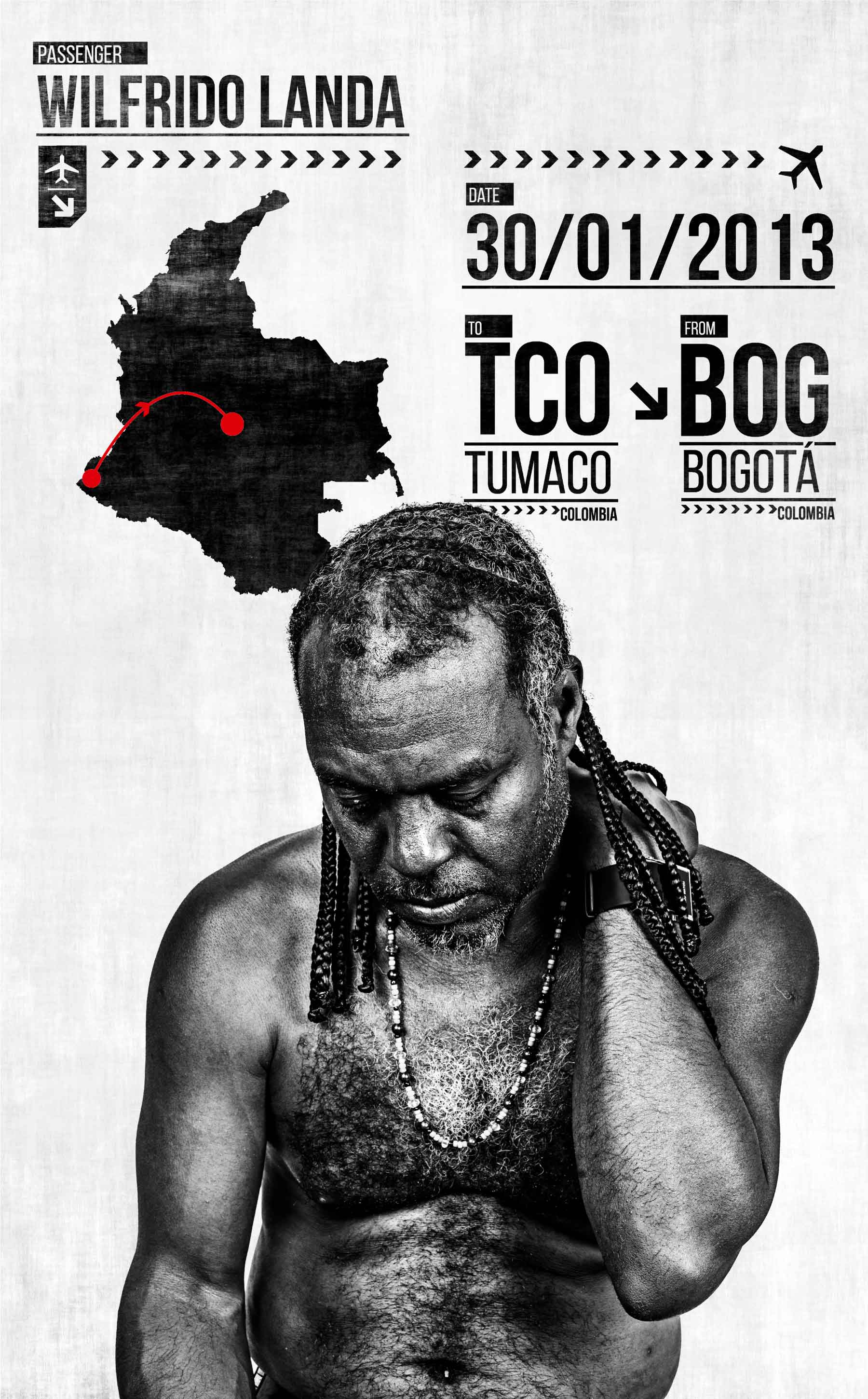

It’s noon and, on the phone, there’s that voice he already knows: El Jefe. Landa tries to ask about the document they’ve mentioned, about Havana. Sharp, caustic answers. You’ve been declared a military target. If I find your shadow, I’ll kill it. The document sent to Havana claiming that I, that FARC are committing crimes in Tumaco: deaths, kidnapping, extortion, drug trafficking. Military target, military target.

Though still unclear on the reasons why this is so, he is clear on the fact that he must flee Tumaco as soon as he can. Pasto? No. Cali? No. The long limbs of El Jefe can reach him there. Bogota! It’s a little before five and the flight to Bogota has been closed. The next one will take off at 7 a.m. Only Landa and Jose, the president of the board, will be on that plane. The money of Tumaco’s government can’t afford to take away immediately anyone else, or their families. The whole governmental board is waiting –10 families, 43 people, all the Council’s board and their families, all huddled close to each other in the room of La Sultana Hotel. A long night filled with whispers, a sleepless night.

Landa and Jose are standing up, grazing each other’s humid arms, their backs against the wall in the small waiting room where passengers crash right after they cross the threshold of the metal detector in La Florida Airport, in Tumaco. Landa carelessly raises his eyes searching for the television screen over the gate’s door. Close by, there are two stooping men. He recognizes them with just one glance. The pen in his pocket draws nervous letters. Jose looks at the piece of paper that Landa slides in front of him at waist level: the one in the blue shirt and the one in the black shirt. Jose flashes a quick look and when his eyes meets the two men, another tear rolls down his cheek.

Hiding, making a call, then another. Outside, amid the luggage, the people and the “Welcome!” signs, they wait –the one in the blue shirt and the one in the black shirt.

Sneak away, disappear in the humdrum and the anonymity of Bogota’s streets. The friend’s house, the other friend’s house, the safe house, the armed guards, the armored cars, the armed men protecting them from the armed men. The travels, then, involved cubicles and forms: the Ombudsman’s Office, the Attorney General’s Office, the Victims’ Unit of Attention and Integral Reparation –the story of displacement told a myriad times.

“Everything stayed in Aguacate. Everything: the house, the livestock, the land. Everything. When the Psychology professor asks about my life project, I reply: It stayed behind in Aguacate.”

Tumaco, 2007

Landa still remembers it. It was in 2002 or 2003. Flor was still tiny back then. Hundreds of men wearing camouflage and carrying weapons started arriving in San Luis Robles, a town in the community, as dawn spread. They took people out of their houses and led them to the central park, for “that was a big meeting and there the community told the members of FARC that they didn’t need them, or the others, or those others, so if they could please go away. That was a lot of bravery from the people to face them not with weapons but with words, to FARC.”

What came after that is known by everyone in Tumaco: coca plantations increased, settlers and scrapers arrived from Putumayo and Caqueta, and with the coca and the profits the business produced, Los Rastrojos also arrived. “They were paramilitary groups, and they weren’t people from the community either. After that, our young men started entering these group and that’s when these people became a fixed presence, though it wasn’t, let’ say, that we gave them auspice to come or stay. Simply, they came for what they came: the coca. They came, picked up their product, and they immediately left.”

In canoes that sailed against the currents of rivers and streams, their bodies pressed against the backs of motorcycle drivers tumbling up and down dirt roads with jungle on one side and coca plantations on the other; from one county to the next, from a neighbor’s house several hours up the mountain through Tumaco’s urban setting to the Mayor’s house, to meet with officials or to guerrilla camps and then back home to the wife, the children, to harvest the palms, to grow them and sell to have something to eat or to buy some of the stuff that the house misses, and then back to the canoe, to the motorcycle, to the roads. That’s what Landa, Jose Felix, and Henry Adolfo’s days looked like. And they were similar to the days of Dargen, Jenny, Segundo, Jesus, Harry, Rubén, Maria, Diogenes, Wilfrido Octavio, Ali, Segundo, Publio, Jesus Francisco, and Yudy.

“Even though they carry weapons, those are people that you can talk to, chat with, or argue with. They understand, you understand, and it’s normal, but for the Colombian government it’s not viable that you, as a leader, as a civilian, do so. It’s not viable. But, well, for people like us who live in the corners, the river beds, who live in the jungle practically forgotten by the State, we have to talk to this people because they are the ones who are in our territory.”

In the counties of Tumaco, the vivid green of the coca started replacing the dull, monotonous color of the African palm plantations, as well as the many-hued green of the virgin forest. The colors of the armed men were also seen more frequently, much closer. There were those who couldn’t leave their territories, those who couldn’t enter them. Three dead people over there, two displaced families further up, trickling deaths here and there. Proposals you couldn’t decline: going to a camp, attending a rally, delivering 50 million pesos. Whispers of death that arrive when the county’s football match is about to begin; whispers that echo in the voices of your acquaintance, and the ball rolls and someone watches the calmness disappear. Men and women, young and old, harassed, threatened, murdered.

“In 2007, the community turns to the leaders, to those of us who were heading the Community Council, and it was them, the community, the one that decided to quit illegality, because they realized that the coca was leading to criminality, to the paramilitaries, and FARC. In other words, all the groups, and there was no communal cohesion, or, rather, the cohesion was disappearing among the young, for they were going if not to this group to this other one, and there were no opportunities to speak for them, be it work, or study. So the community made the decision to quit this, but then they tell us, the leaders: What are we going to do? If we quit coca, which is what is giving us for the rice, the agua de panela, then, how are we going to survive?”

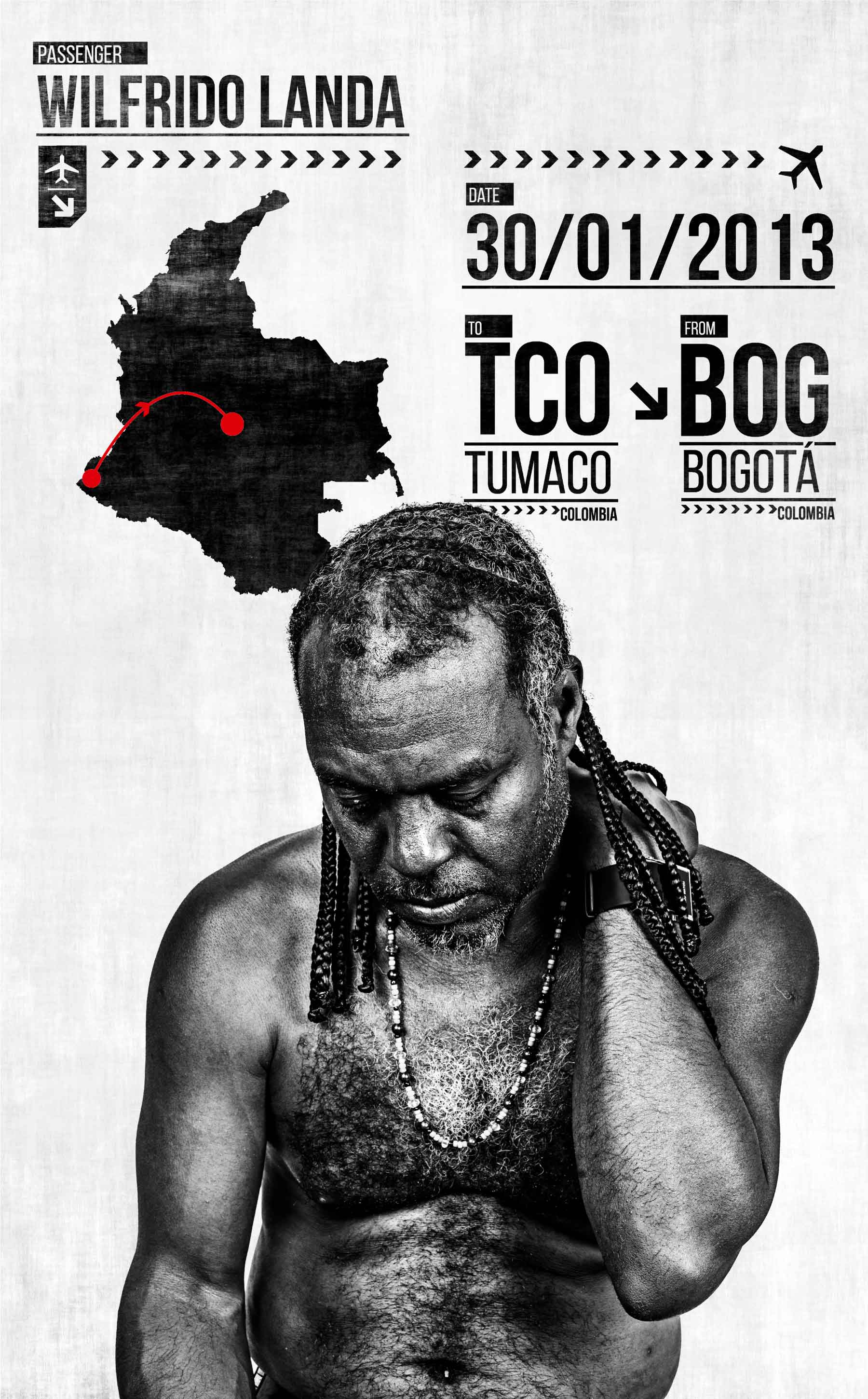

Tumaco – EE.UU, 2011.

The biggest, the biggest of the planes that travels from Cali to Bogota. Then, during the course of a month, there were smaller ones that land one by one in eight different airports in the United States. One of the passengers, Landa, the legal representative of Rescate-Las Varas, steps off the planes. He walks the halls and enters the offices of the State Department, the Justice Department, the Police and the Pentagon. The word coca is uttered in Spanish and after it: Yes, it can be done; territory; collective; county; black communities; council; cacao; subsistence crops. Perhaps those that listen to him notice some of what those traversing the roads of Tumaco or other faraway corners of Colombia can see: next to the coca plants, there are no cartoon drug dealers like those sketched in movies or television series. Those standing by the coca bushes –not by the cocaine loads—are farmers, people with complete names who know the plants, the land, the forest, and the water.

Yes we can, Las Varas was the name given to the program conceived by the community and sponsored by the Governorship of Nariño.

“We started replacing coca in 1,252 hectares that depended on 1,252 families that, back then, were part of the Community Council. [The hectares that were previously planted with coca] we changed them for food safety. We planted cassava, plantain, tomato, beans, corn, rice. Each family sowed a hectare, but the subsistence crops weren’t everything. A percentage of the subsistence crops –a percentage was for transformation and another for barter. That is, if you grew corn and I grew rice, then we traded. Around 10% of these products, what was left over, was sold at the municipal level.”

Yes we can entailed, apart from that, an agreement with the national government that included the end of the aerial aspersion of poison over their jungles, crops, people, and coca plantations. The government was also bound to stop the forced manual eradication of coca. The argument: the community itself would voluntarily pull out the coca plants and replace them with crops.

“They [the United States officials] were amazed when I told them that we were doing all that surrounded by FARC, and that back then we told the guerrillas: This is our collective, ancestral territory. It belongs to us. Here, we are the law. They [the United States officials] asked us where we got the strength to do that. And I answered: The strength lies with community because back then the community supported us. It was the whole community that wanted to quit that fancy for coca. We were a territory that wanted to get rid of illegality through alternative proposals that didn’t come from a professional’s desk. Rather, they were proposals that were borne of the community’s perspective. That opened a lot of doors at the international level.”

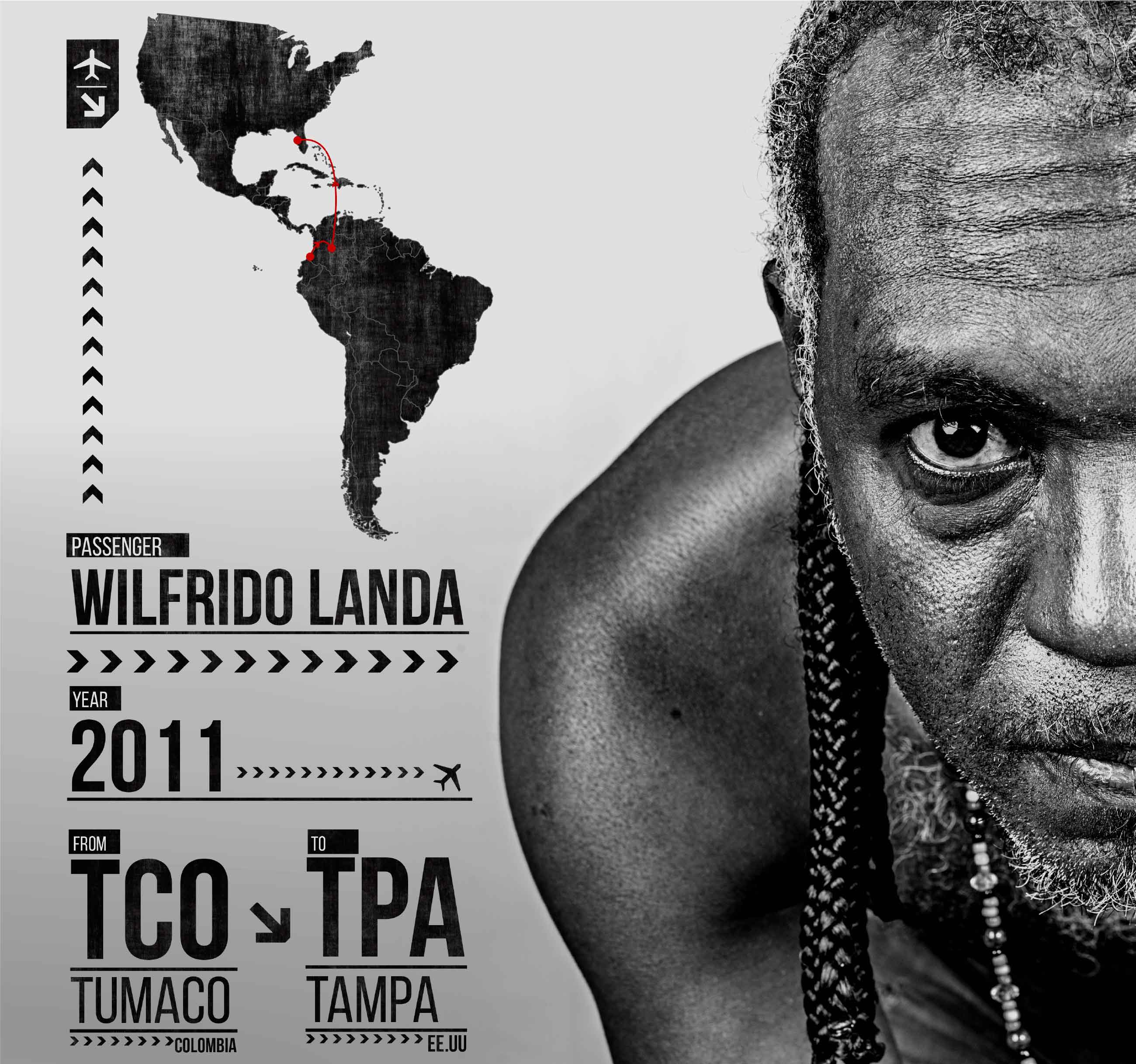

Bogotá- Cuba, 2014.

When they land in the island, they step down the stairwell and right there, by the plane, they meet Victoria Sandino and Marcos Calarca of FARC, a Cuban delegation and representatives from the Norwegian Embassy, who extend their hands and greet them one by one. In Cuban government SUVs, they travel the 18 kilometers that separate them from the city.

“When we arrived, they led us to a room where this people, more formal now, greet us, and they start to chat with us: that we shouldn’t be afraid; that we ought to say everything; that they want to hear us, the victims; that they want us to share our pain and that right away they’ll ask for our forgiveness in the room; that we should forgive them for all the harm they’ve done to each one of us, to Colombia –that’s the first they thing they tell us, and we felt, like, How did this happen? Because you came there with the presumption of meeting with them. After that, we went to a room where there is a… that is, there was a… where all the journalists were, and there we gave a statement.”

Out of the 8,405,265 registered victims of Colombia’s armed conflict*, 60 were organized in five groups and were invited to fly to Havana between August and December of 2014. There, with their voices, they were meant to “echo the whole universe of human rights violations and infractions of international human rights laws,” just like the negotiations between FARC and the Colombian government called for to strengthen the peace accords and highlight the importance of victims’ needs. **

That’s the official figure registered in the Registro Único de Víctimas (Sole Victims’ Register) of the Victims’ Unit. The number includes the cases that took place between January 1, 1985 and April 1, 2017.

** The selection was made by the UNDP(United Nations Development Programme), the National University of Colombia, and the Episcopal Conference at the behest of Colombian government and FARC negotiators.

Threats, attacks, disappearances, extrajudicial executions, murders, massacres, antipersonnel mines, forced recruitments, kidnappings, torture, forced displacement, sexual violence.

Among the travelers, there were civilians, military personnel, businessmen, union representatives, religious men and women, academics, journalists. Not only were there people directly affected by the Armed Forces and FARC; there were also those who suffered at the hands of the paramilitaries, the ELN (National Liberation Army), criminal gangs, and a case of someone who was affected by multinational mining companies. Women, men, people representing children, representatives of the LGBTI community, representatives of the disabled population, of the black communities, of the indigenous people, and a peasant leader.

“I was chosen to go there for the case of forced displacement of the Governmental Board (of Rescate-Las Varas). They called me one Wednesday, they told that me I’d been chosen to go to Havana in the fourth delegation, whether I was willing to go, that, well, this couldn’t be discussed with anyone –not the press, not anyone, anyone, no one, not even my wife. I said yes: of course I was willing to travel. That same day, in the evening, I told Soledad. She said: If you are willing and you want to go, go.”

Eleven of the twelve people who formed the fourth group were gathered in a hotel in Bogota’s north before boarding the plane to Cuba. The twelfth guest was Tulio Murillo, a FARC guerilla fighter who would spoke through a video feed in a Colombian prison as a victim of threats.

In Havana, after the protocolary greetings, they were led to a hotel. At 8 a.m., an event awaited them were each and every one would have a few minutes to tell the story of what they had lived.

“That night was never-ending; that is, I didn’t know what to say, I didn’t know. Everything I had written to say, all the script –I’d forgotten it. The next day, we woke at 7 a.m. and an SUV picked us up to take us to the room where we were supposed to speak.”

The 11 were lined up in the order in which they were supposed to go in, one by one, to talk for 15 minutes about the fact, or the facts, that had changed their lives forever.

“I was maybe in the tenth position, yes, in the tenth position. There was another man and then Tulio’s video presentation and that was it, it was my turn, the 15 minutes that were assigned to me. But when you start speaking, all these ideas come to you and all that happened. And I started speaking and, all of a sudden, the priest raised his hand there –that I should look at my watch because the 15 minutes were almost up. But it felt like I had spoken for only a minute, I told the priest, and the fact is I haven’t finished telling this people what I have to tell them. They gave five more minutes and that was it.”

Following everyone’s interventions, lunch was served. Landa sat in front of a United Nations official who suddenly pointed out with her finger, signaling him to turn around because someone wanted to talk to him. “It was Ivan Marquez. He wanted to sit at their table. He asked me to tell them my case in detail. I said: In Tumaco, the woman who sells [cell phone] minutes is extorted; the man who sells fish is extorted; there, a lot of human rights violations are being carried out in unbelievable ways. I told them about the dismemberments, because there they dismembered people. I told them all that and I told them about my case in detail. That man was impressed. He said: We do know that we have some comrades that are doing things that are beyond our scopes and beyond our mandates, but we are going to remedy that. That’s how he said it. Six months later, the Army killed alias ‘Oliver,’ one of the commanders. By that time, ‘El Jefe,’ the person who had forced us to leave Tumaco, had already been captured.”

On February 25, 2014, Landa, Soledad, and many others watched ‘El Jefe’ on television and read headlines about him in national newspapers. The “Terror of Tumaco” has fallen, a drug trafficking kingpin with links to FARC. In Tumaco’s jungle area, alias ‘El Jefe’ has fallen. The guerrilla fighter is being investigated for several attacks. A rifle, a 5.6mm gun, six USB flash drives, and cartridges were seized. The alleged guerrilla fighter had said that they would never capture him.

That Tuesday, the National Army reported the capture of aka ‘El Jefe’, the third commander of FARC’s Daniel Aldana Column, in the county of San Pedro del Vino, an area located between the Mejicano and Mira rivers, two hours from Nariño’s port.

In December 2015, Landa and nine out of the 60 other travelers that had been in Havana a year before returned to the city. This time, they were guests at the event that would reveal the agreements related to victims and a few details about the new transitional justice model that participants in the armed conflict would face in Colombia.

In the first months of 2016, ‘El Jefe’ contacted Landa again. This time he called from the National Prison of Palmira and reached him through some relatives. “I was in a bus and he called me. I stepped off and we talked for about 20 minutes. He asked me to forgive him, he apologized, that is, that it was all a mistake he made, but he wants to fix things and, if I am interested, he will send his lawyer to arrange a visit in jail. I said: No, but… you know that we are a community and as such many of us left the territory, so if I go the others go as well. That was in early 2016. In mid-September, a district attorney who was leading his case contacted us and told us that he had a proposal. The proposal consisted in making a public act acknowledging his responsibility, returning some of the resources that he had taken from the Community Council in the beginning, and asking the community for forgiveness for the damage he had done by displacing us and admitting that it wasn’t like some said, like people said: that FARC had displaced us from our territory because we had stolen the community’s resources.

Landa, on his side of the phone, also said that the admission of guilt shouldn’t be done through a video feed, as other FARC guerrillas in jail had done when asking for forgiveness for the deaths of two leaders of the black communities *. No, he said, it had to be personal, face to face with the community, which implied that somehow ‘El Jefe’, jailed nearly 700 kilometers away, would have to reach the territory of the Rescate-Las Varas Community Council to, this time, ask for forgiveness so as to fulfill the requirements of justice put forward by the agreements made by FARC and the Colombian government.

José Hamilton Castillo, the man who killed Miller Angulo Riveros (a member of the Municipal Board of Tumaco’s Victims and of the Departmental Board of Victims murdered on December 1, 2012), and Juan Carlos Caicedo, who killed Gilmer Genaro Garcia (Legal Representative of the Alto Mira y Frontera Community Council, murdered on August 3, 2015), both accepted a plea deal with Colombian justice that included that act of contrition.

“That never happened because his lawyer quit. That hasn’t happened because he has changed lawyers twice and they tell him not to go forward with that acknowledgment [of guilt]… that is, not to fulfill his agreement with us, an agreement that a district attorney wrote and brought here, to the Court of Justice.”

‘El Jefe’ was condemned to 17 years for extortion, rebellion, and terrorism, but when the transitional justice system is in effect he’ll be free in around 8 years. Though the peace accords that are meant to solve the conflict speak of truth, reparation and non- repetition, there are strategies to deal with the fear of reprisals that grows like weed among people in the territories.

“We don’t want to pursue the process for forced displacement that would target him because our family is there in the territory and we must return to Tumaco someday. So if he’s already been caught for his affairs, let him defend himself however he can for what he has already been impinged. Either way, he already forced us out and the project that we had has, let’s say, already been thwarted. Now we are starting anew and, well, if we are to have new problems, it’s better to remain the way we are.”

In Bogota’s airport, the place where, nowadays, all his travels begin, Landa walks among the other passengers hauling his suitcase and his memories.

“The aqueduct we were building in Las Varas was left unfinished, and many other things like that. Coca nowadays is double what it used to be before, when we removed it. Coca from foreigners and from members of the community. We started a process with International Cooperation, but the Colombian State didn’t live up to the commitment. In other words, the resources we needed for the projects we had never arrived, were never met, and that forced the communities, which were hopeful, well, nothing arrived, so what else can you do? Plant coca.”

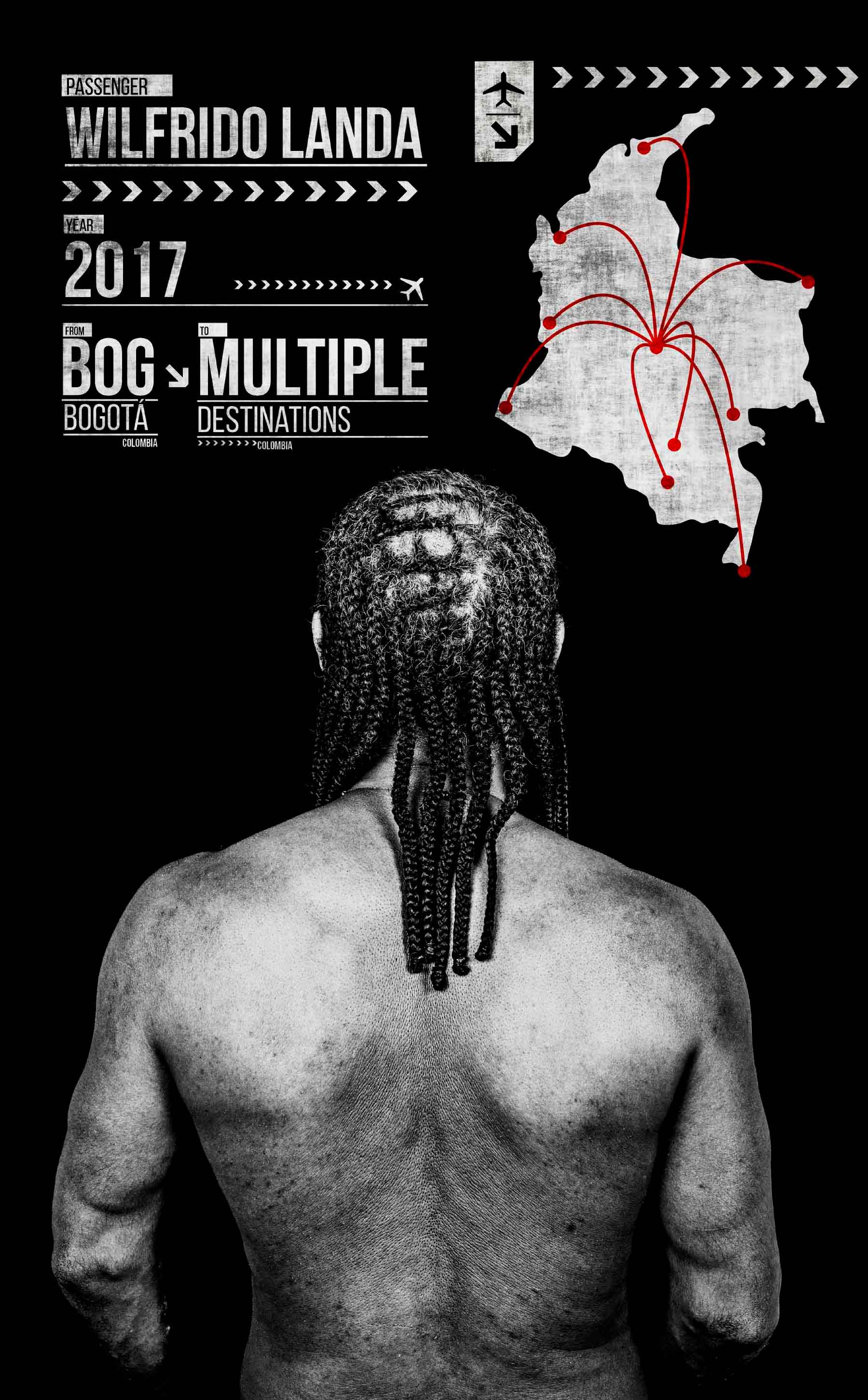

In Bogota, Soledad studied theology and she now words at a kindergarten in the south of the city. Flor goes to school and she is about to dress up as quinceañera princess. At night, Landa studies to become a social worker, and, by day, he works with the Victims’ Unit, handling the policies that guide the attention protocols with an ethnic and differential focus. Landa lands in cities that rise by the shores of the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, in the Amazon jungles, in the Andean mountains. The plane, the SUV, the beast, and his feet, protected by rubber boots –they all take Landa to do his work in the territories of the blacks, the indigenous, and the raizales. They take him there, but they still don’t take him back to Aguacate.

“Right now, the plans are to end the studies, consolidate myself at work, and return to Tumaco by the end of the year, God willing. To visit.”

“El Jefe” is not the alias used by the real person referred to in the story. It has been changed for security reasons.